Skull fractures

Introduction

Skull fractures only occur after high impact injuries, given the skull is difficult to break. As with most traumas, other injuries should be suspected and before transporting a patient immobilization performed to protect the spinal cord.

Note also that the impact on the head causing the fracture may also cause brain injury. Patient that have experienced blows to their head are at risk for concussions, contusions, hematomas and diffuse axial injury (DAI). These injuries should be expected alongside skull fractures.

Linear fractures

Most common type of skull fracture. These can usually be seen in a CT scan; the patients will then be kept for observation for a few days and then released without complication. These fractures cannot be identified in the field any major blow to the head should give you reason to suspect a fracture. Though, even if identification were possible, no interventions can be done to decrease morbidity in these patients.

Diastatic skull fractures

Usually seen in infants or newborns, these are fractures along suture lines of the skull whilst it is still in development. These can become dangerous if meninges protrude outside the breakage in the skull and develop a leptomeningeal cyst that keeps the fracture open and often may expand it. These will often be called growing fractures given they appear to grow with the child.

Basilar fractures

Basilar fractures represent possibly the most dangerous type of cranial fracture. They are fractures that occur on the base of the skull. They are most commonly identified by bruising around the eyes and behind the ears, cerebral spinal fluid leakage from the ears/nose and apparent cranial nerve damage. Depending on the area of breakage the fracture may damage the inner ear structures as well. Symptoms change depending on where the fracture occurs but bear in mind that several fractures may be present and these symptoms are clues not diagnostic tools, imaging is always needed to locate basilar fractures.

Anterior fossa fractures:

- Loss of sense of smell or anosmia

- Epistaxis with/without CSF (detectable with the halo sign)

- Subconjunctival bleeding (apparent hemorrhage in the sclera)

- Visual disturbances/ difficulty with eye movement

- Raccoon eyes (Ecchymosis around the orbit)

- Loss of sensation to the upper face

Middle Fossa fractures:

- Discharge from the ears.

- Difficulty hearing/Hearing ringing

- Dropping in the face

- Blood in the tympanic cavity

Posterior fossa fractures:

- Battle sign(s)

- Absence of gag reflex

- Possible damage to the carotid artery, vertebral artery or brain stem

These fractures are dangerous for several reasons:

One, the bones of the base of the skull are the thickest and hardest to break. If they do break, it is usually a sign of significant blow to the head. The more force is used against the skull the higher the risk of injury.

Two, many important structures are located at the base of the skull and damage to the cranial nerves, inner ear structures or brain stem can lead to major morbidity if not mortality.

For emergency responders, it is most important to remember that nothing may be inserted into the nasal cavity with this kind of fracture due to the risk of damaging brain tissue due to the lack of structure in the skull.

Depressed skull fracture

In a depressed skull fracture the skull caves in where the impact occurred. This puts the brain at risk, it may create a lesion in the dura and possibly even damage underlying brain tissue. This may put the patient at higher risk for meningitis and brain damage.

Face fractures

Midface fractures

Signs include edema, lengthening of the face, epistaxis or rhinorrhea of CSF & other general signs of trauma to the face. The nose and other facial apexes may become flattened.

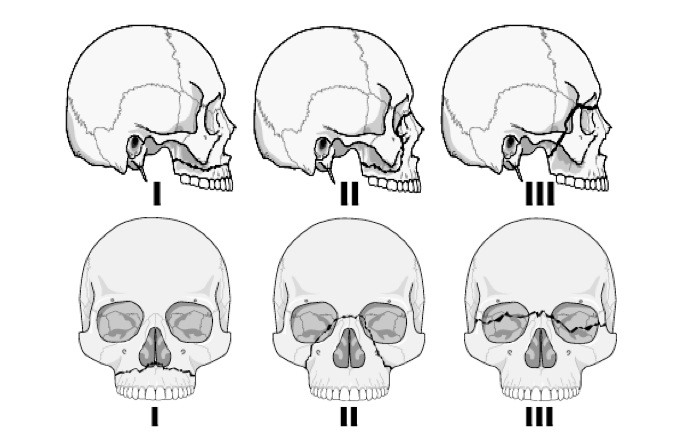

Le fort fractures:

Le fort 1: Break of the Maxilla.

Le fort 2: Over the nasal arch and down the maxilla.

Le fort 3: Over the nasal arch and through the orbits, separating facial bones from the rest of the skull. The break occurs in between the sphenoid/zygomatic bones and the frontal bone.

Airway management with these patients is difficult because of the collapsed structures of the face, swelling and bleeding. Any devices inserted through the nose can be a danger to these patients because brain tissue may not be protected by its usual structures and so they are therefore contraindicated.

Zygomatic and orbital fractures

Zygomatic and orbital fractures can be difficult to distinguish. These typically occur alongside other facial fractures such as le fort fractures.

If the break occurs at the base of the orbit, soft tissue may be pushed into the maxillary sinus. These injuries usually heal on their own but if diplopia or pain continue, long after the fracture has healed, surgical intervention may be required.

Nasal fractures

Weakest bone structure in the face and thus most likely to break.

Management and references

Patients with skull fractures should be immobilized for fear of cervical spinal fractures.

Airway management can be especially difficult with facial fractures so having suction, an OPA and intubation equipment ready could save your patients life. If a midface and basal fracture are not suspected use of an NPA is indicated in patients with reduced level of consciousness that do not tolerate OPA’s.

If bleeding is severe consider hemorrhagic shock and treatment for shock. If epistaxis is present, make sure the patient will not aspirate by making them lean forward (if possible).

Wilberger, J. E., Endowed, J., & Dupre, D. A. (2015). Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). SpringerReference. doi:10.1007/springerreference_183102

QINGZENG, S., YINGCHUN, S., & FENGFEI, Z. (2017). Pediatric skull fractures and intracranial injuries (Review). Experimental & Therapeutic Medicine, 14(3), 1871-1874. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4715

Morgan, B. (n.d.). Critical Care Trauma Centre. Retrieved September 25, 2017, from http://www.lhsc.on.ca/Health_Professionals/CCTC/edubriefs/baseskull.htm

American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2017, from https://aapos.org/terms/conditions/28

Sanders, M. J. (n.d.). Mosby's Paramedic Textbook (Fourth ed.). Louis, MI: Mosby.